The Diphtheria disaster at Medellin, Colombia.

Diphtheria of a virulent type had been present in the district. In 1928, 45 of 105 patients died; in 1929, 68 of 109; and in 1930, 30 of 271. In consequence it was decided to test children by the Schick method and to immunize them with formalinized diphtheria toxin – that is, formol-toxoid. All went well until the immunization of a group of 48 children aged 2 to 7 at Las Salas Cunas.

Formol-toxoid prepared locally was used, and all injections were made sucutaneously into the scapular region. The first and second injections were uneventful, 0.5 c.cm on October 7th, 1930, and 1 c.cm. 17 days later.

For the third injection, of 1.5 c.cm three weeks later, a bottle of toxin was used in error instead of formol-toxoid. Its minimum lethal dose was, when freshly prepared, 0.002 c.cm. At the time it was injected into the children the m.l.d. was found to be 0.004 c.cm., the children thus receiving about three hundred and seventy-five times the amount of toxin that would kill a guinea-pig.

The injection had been given around 2pm. Many of the children were seriously ill during the night. During the next afternoon one child died. Between 5 and 7 o’clock about fifteen children were traced and given between 8,000 and 12,000 units of antitoxin. During that night three children died. Within sixty hours of the injection fourteen children had died. Six days later one more died, and six weeks later one died of post-diphtheritic paralysis.

The general picture was one of toxaemia. The children suffered from pain at the site of the injection, with fever, and with restlessness often going on to convulsions; some reported vomiting, and a few diarrhoea. Three children had much swelling, ulceration and necrosis at the injection site. Three more had severe local pain, and post-diphtheritic paralysis, but finally recovered.

It is striking that false membrane in the throat, apparently typical in character, was reported in ten children. It was first detected 48 hours after the injection.

In the laboratory at Medellin the bottle of toxin which was responsible for the deaths was kept in the same ice-chest with a similar bottle containing the toxoid used in the first two injections. The possibility of disastrous human error under such conditions is obvious.

Extracted from the original account published in the British Medical Journal: Br Med J 1931 ii 27-8

Commentary

Immunisation has saved millions of lives worldwide, and vaccine mishaps are exceptionally rare. Serious prescribing and dispensing accidents are much more likely to be due to an error with a drug.

Nevertheless, the author in 1931 was able to point to three other occasions when similar errors had been made. This was because raw diphtheria toxin was used for the Schick test at the time, so kept in medical facilities. In order to select children for immunisation, a tiny amount of toxin was injected intradermally to show whether subjects were already immune to diphtheria toxin. Heat inactivated toxin was injected at a second site as a control.

The scale of the disaster at Medellin is terrifying, but history records many comparable errors since, from storing different drugs in similar packaging, in the same locations, or with labelling open to misinterpretation. The anonymous correspondent in this article urges openness about such mishaps, so that we can learn and prevent future episodes. 85 years later we are better at this, but it is still not clear that it always occurs.

It seems likely that the survivors here were protected by the immunity already gained from the first two injections.

One of Mikhail Bulgakov’s Young Doctor’s Notebook stories from the same era, The Steel Windpipe, conveys the horrors of severe diphtheria.

Further info

- Diphtheria immunisation was developed in the 1920s. Diphtheria was a serious public health problem, in the 1930s still the third most common cause of childhood deaths in England and Wales.

- The history of vaccines posted by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia has a lot more fascinating detail, of the development of vaccine, adjuvants, and the famous Nenama to Nome dog sled mission in harsh conditions to deliver antitoxin to an epidemic in Alaska in 1925.

- The Schick test (Wikipedia)

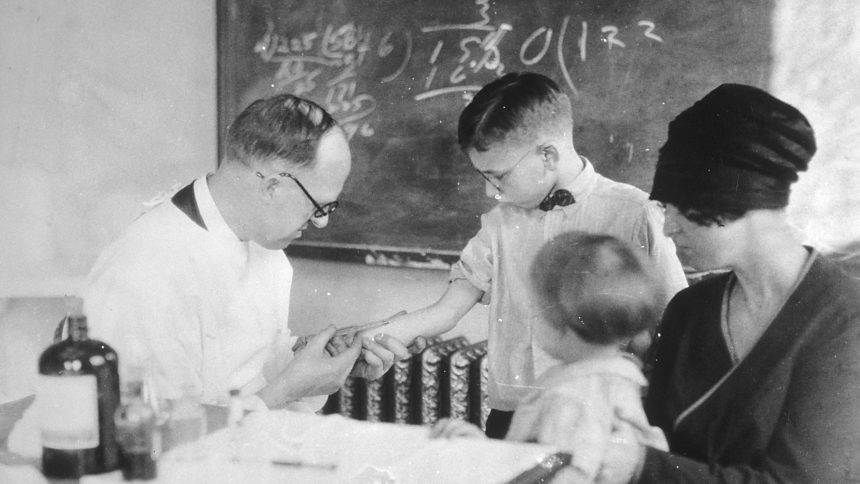

- Featured image: A boy receives an injection of diluted toxin for the Schick test in 1915. via Wikimedia Commons

Contributed by

Neil Turner

Rate this post

More like this

The Steel Windpipe (Mikhail Bulghakov story)