A dying child in rural Russia in 1916, by Mikhail Bulghakov.

At eleven o’clock that night a little girl was brought. The mother’s face was contorted with noiseless weeping. When she had thrown off her sheepskin coat and shawl and unwrapped the bundle, I saw a little girl of about three years old. For a while the sight of her made me forget operative surgery, my loneliness, the load of useless knowledge acquired at university: it was all completely effaced by the beauty of this baby girl. But in the depths of her eyes was a strange cloudiness and I recognised it as terror – the child could not breathe.

Her throat was contracting into hollows with each breath, her veins were swollen and her face was turning from pink to a pale lilac. I managed to look into the girl’s throat by the light of the pressure-lamp. I had never seen diphtheria before except for mild, forgettable cases. Her throat was full of ragged, pulsating, white substance. The little girl suddenly breathed out and spat in my face, but I was so absorbed that I did not flinch.

‘Well now,’ I said, astonished at my own calm. ‘This is the situation: it’s late, and the little girl is dying. Nothing will help her except one thing – an operation.’

I was appalled, wondering why I had said this, but I could not help saying it. The thought flashed through my mind: ‘What if she agrees to it?’

‘I’ll have to cut open her throat and put in a silver pipe so that she can breathe, and then maybe we can save her,’ I explained.

The girl’s mother and an older woman disagree about whether to consent to this drastic procedure, but finally the mother agrees, while the old woman still rails against it.

I rushed to my room through a swirling, blinding snowstorm. Counting the minutes, I grabbed a book and found an illustration of a tracheotomy. I started reading the text, but could take none of it in – the words seemed to jump before my eyes. I had never seen a tracheotomy performed. Feeling that I had suddenly been burdened with a most fearful and difficult task, I went back to the hospital, oblivious of the snowstorm.

They strapped her down, washed her throat and painted it with iodine. With the scalpel I made a vertical incision down the swollen white throat. Not one drop of blood emerged. Slowly, trying to remember the illustrations in my textbooks, I started to part the delicate tissues with the blunt probe. At once dark blood gushed out from the lower end of the wound, flooding it instantly and pouring down her neck. The feldsher* started to staunch it with swabs but could not stop the flow. Calling to mind everything I had seen at university, I set about clamping the edges of the wound with forceps, but this did no good either.

I went cold and my forehead broke out in a sweat. I bitterly regretted studying medicine and having landed myself in this wilderness. In angry desperation I jabbed the forceps haphazardly into the region of the wound, snapped them shut and the flow of blood stopped immediately. We swabbed the wound with pieces of gauze; now it faced me clean and absolutely incomprehensible.

There was no windpipe anywhere to be seen. This wound of mine was quite unlike any illustration. I poked aimlessly in it, first with the scalpel and then with the probe, searching for the windpipe. After two minutes of this, I despaired of finding it. ‘This is the end,’ I thought. ‘Why did I ever do this? I needn’t have offered to do the operation, and Lidka could have died quietly in the ward. As it is she will die with her throat slit open, and I can never prove that she would have died anyway.’ The midwife wiped my brow in silence. As I thought this I pictured the mother’s eyes.

I picked up the knife again and made a deep, undirected slash into Lidka’s neck. The tissues parted and to my surprise the windpipe appeared before me.

‘Hooks!’ I croaked hoarsely.

The feldsher handed them to me. I pierced each side with a hook and handed one of them to him. I thrust the sharp knife between the greyish ringlets of the windpipe – and froze in horror. The windpipe was coming out of the incision and the feldsher appeared to be tearing it out. The two midwives gasped and I looked up and saw what was the matter: the feldsher had fainted. ‘It’s fate,’ I thought, ‘everything’s against me. We’ve certainly murdered Lidka now. As soon as I get back to my room, I’ll shoot myself.’ The older midwife, who was evidently very experienced, pounced on the feldsher and tore the hook out of his hand, saying through her clenched teeth: ‘Go on, doctor …’

The silver tube slid in easily but Lidka remained motionless. The air did not flow into her windpipe as it should have done. I sighed deeply and stopped: I had done all I could. I felt like begging someone’s forgiveness for having been so thoughtless as to study medicine. Silence reigned. I could see Lidka turning blue. I was just about to give up and weep, when the child suddenly gave a violent convulsion, expelled a fountain of disgusting clotted matter through the tube, and the air whistled into her windpipe.’

Lidka recovered.

I grew more experienced. My practice grew till I had a hundred and ten patients in one day. The senior midwife said to me:

‘It’s the tracheotomy that has brought you all these patients. Do you know what they’re saying in the villages? The story goes that when Lidka was ill a steel throat was put into her instead of her own and sewn up. People go to her village especially to look at her.’

‘So they think she’s living with a steel one now, do they?’ I enquired.

‘That’s right. But you were wonderful doctor. You did it so coolly, it was wonderful to watch’.

- Feldsher: Physician’s assistant.

Extracted from The Steel Windpipe, one of the stories in A Country Doctor’s Notebook by Mikhail Bulghakov, translated by Michael Glenny (1975).

Commentary

“Twenty-four years old, having qualified a mere two months ago, I had been placed in charge of the Muryovo hospital.”

These remarkable stories of a new doctor who feels inadequately prepared for his posting to rural Russia were published in the 1920s and rediscovered in the 1970s. The extreme circumstances render particularly vividly the anxieties of new medical practice, the highs and the lows. These themes resonate strongly still. Most but not all of his tales have an upbeat ending, as this one does – but so closely that you can easily feel the ‘what if’.

A companion story in the book, Morphine, describes one of his successors in the remote post being driven to addiction and suicide.

Further info

- More about Bulghakov and A Country Doctor’s notebook in the commentary at Suppose they bring me a hernia.

- Commentary by Jack Coulehan in the NYU Litmed database; and Commentary by Michael Bloor in a Hektoen International post. Both of these draw attention to the moving, if tough story The Use of Force by William Carlos Williams, which we also feature.

- Image above: A ghostly skeleton trying to strangle a sick child, representing diphtheria. Watercolour by Richard Tennant Cooper, 1910. Wellcome Images (V0017055)

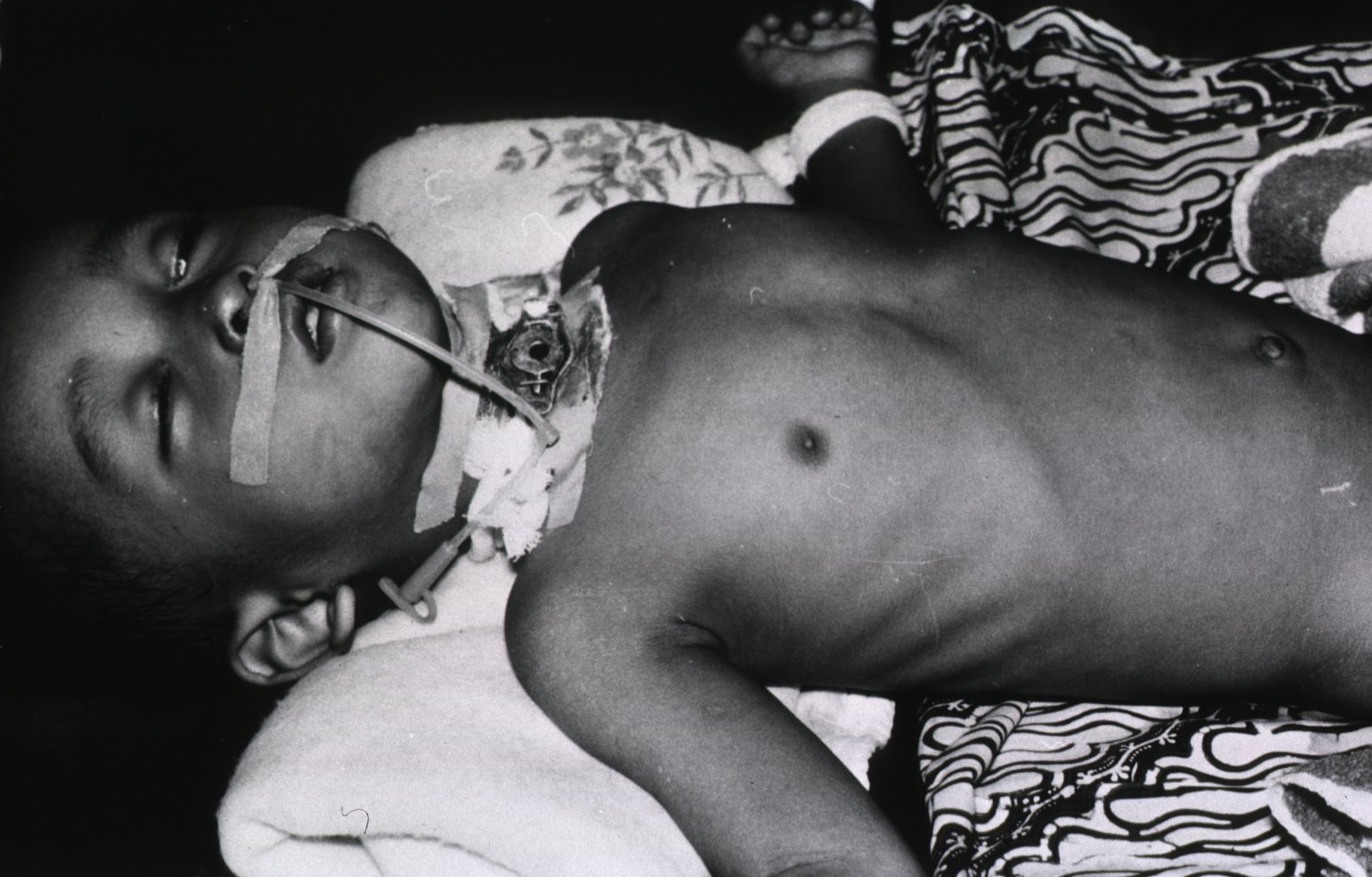

- The image below is ‘A throat operation kept alive this little Indonesian victim of Diphtheria‘ (WHO, L.Mallovski)

Contributed by

Neil Turner

Rate this post

More like this

Suppose they bring me a hernia (The Embroidered Towel) – another from A Country Doctor’s Notebook