I this day began to feel unaccountable alarm of unexpected evil: a little heat in the members of my body sacred to Cupid, very like a symptom of that distemper with which Venus, when cross, takes it into her head to plague her votaries. But then I have no risks. I have been with no woman but Louisa; I’m sure she could not have such a thing.

Wednesday 19 January 1763

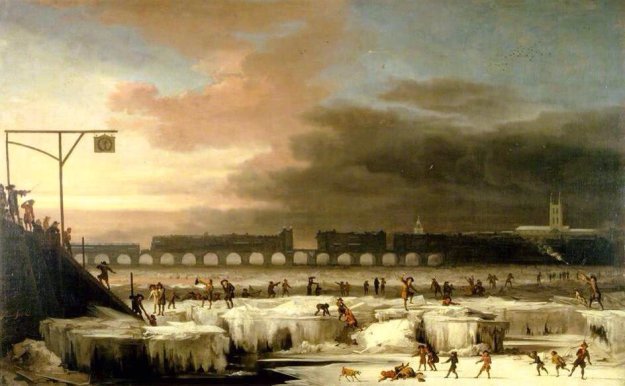

We turned down Gracechurch Street and went upon the top of London Bridge, from whence we viewed with a pleasing horror the rude and terrible appearance of the river, partly froze up, partly covered with enormous shoals of floating ice which often crashed against each other. As we went along, I felt the symptoms increase, which was very confounding and very distressing to me.

The evening was passed most cheerfully. When I got home, though, then came sorrow. Too, too plain was Signor Gonorrhoea. Yet I could scarce believe it, and determined to go to friend Douglas next day.

Thursday 20 January

I rose very disconsolate, having rested very ill by the poisonous infection raging in my veins and anxiety and vaccination boiling in my breast.Am I now to be laid up for many weeks to suffer extreme pain and full confinement, to be debarred all the comforts and pleasures of life? And then must I have my poor pockets drained by the unavoidable expense of it? And then am I prevented from making love to Lady Mirabel, or any other woman of fashion? Oh dear, oh dear! What a cursed thing this is! What a miserable creature am I!

Thus ended my intrigue with the fair Louisa, which I flattered myself so much with, and from which I expected at least a winter’s safe copulation. It is indeed a very hard. I cannot say, like young fellows who get themselves clapped in a boarding house, that I will take better care again. For I really did take care. However, since I am fairly trapped, let me make the best of it. I have not got it from imprudence. It is merely the chance of war.

Saturday 22 January

A distemper of this kind is more dreadful to me than most people. I am of a warm Constitution: a complexion, as physicians say, exceedingly amorous, and therefore suck the poison more deeply. I have had two visitations of this calamity. The first lasted 10 weeks. The second four months.Friday 4 February

I had been very bad all night, I lay in direful apprehension that my testicle, which formerly was ill, was again swelled.Sunday 27 February

My disorder is over now. Nothing but a gleet remained, which gave me no pain and which could be removed in three days.

From James Boswell, A London Journal, 1762-3.

Commentary

A patient who is his own worst enemy: the smoker, the addict, the over-eater. Boswell shows no real regret or intent to alter his behaviour.

Boswell’s extraordinarily frank confessional style makes his journal a fascinating read. He gives a famously detailed account of one of his many encounters with gonorrhoea long before effective treatments. The episodes were a consequence of his apparent obsession with frequent, usually casual sexual activity. This was often with prostitutes, but not in this case – to his chagrin; he feels hard done by. His friend Douglas was a doctor. It is astonishing and alarming that he continued this behaviour, sometimes ‘armoured’ with a crude condom of the times, despite the very limited efficacy of treatments (mostly mercurial drugs?).

Boswell is best known for his later account of Samuel Johnson’s life, but he was sought after himself: “Boswell was the most charming companion in the world, and London becomes his dining-room and his playground, his club and his confessional” (Peter Ackroyd, in his introduction to the 1950 edition). He mixed with the heights of society and culture, and writes amusingly and without reserve about all that he saw and thought. ‘Louisa’ was however a pseudonym. He blamed her bitterly for ‘deceiving him’, the concept of asymptomatic carriage being apparently not known.

He came to London from the family estate at Auchinleck, Ayrshire, on an unsuccessful attempt to purchase a military commission. He later returned repeatedly, when he carried on much the same behaviour.

Further Info

- Boswell and London prostitutes – simultaneously fascinating and horrifying, luridly recounted in the Tea in a Teacup blog, which is worth exploring in its own right. It describes assumptions, precautions, and background.

- jamesboswell.info is devoted to the eccentric life of Boswell.

- Boswell’s London Journal online – 1950 edition – not all pages available.

- A comparison of available editions of the Journal. The 1950 edition was first but the 2010 Penguin version edited by Douglas Turnbull is often recommended. Boswell’s other journals – some available online. The London Journal and a number of other papers were only published in 1950, having been concealed for almost two hundred years. The story is told in the preface to the 1950 edition.

- Auchinleck House, the country home of the Boswells, into which the family was moving from their ancient castle at this time. Now you can stay there. Boswell’s father was a prominent and successful ‘judge and killjoy’ (Ackroyd again) who had scant regard for his son’s aspirations and flights.

- The featured images are from Swell’s NIght Guide to the Bowers of Venus, c1830 (British Library) and The Frozen Thames of 1677, by Abraham Hondius (Museum of London; via Wikimedia Commons).

Contributed by

Neil Turner

Rate this post